Omegle.com allows people from around the world to converse with each other “anonymously”. It is one of those sites that let you start a text or video chat with someone online and consequentially makes you doubt the intelligence of man kind. On sites like this, text chat follows the famous “Greater Internet Fuckwad Theory” and the video chat is… Well it’s probably a phallus. Omegle started as a way for strangers to connect and talk with each other, but has since devolved and the chance of finding some meaningful conversation on it is minuscule which is a shame because random chatting is a fun concept. I would add a premium feature that administers an IQ test and matches you to someone according to that but that is an idea for a different time.

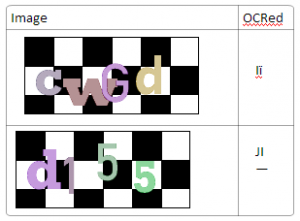

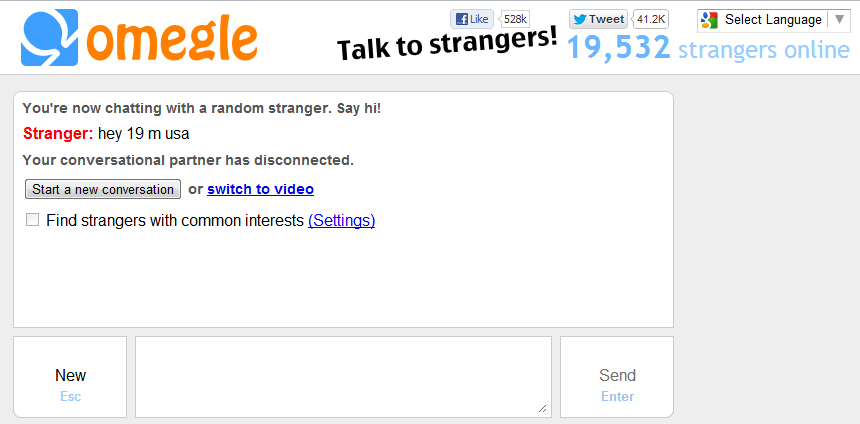

A typical Omegle chat

When I first discovered Omegle I quickly got tired of trying to find someone to talk to. The idea of Omegle is not new or revolutionary. IRC and chat rooms were there before but this made it as easy as can be. Since I already spent a ton of time in online social communities with people who have the same interests as me I dismissed it as a cost efficient way of communicating. I did find a use for Omegle though – there was nothing preventing me from spying on a random conversation and recording it. A nice challenge and it seemed fun. This was years before Omegle itself introduced the “Spy mode” so I guess there is something there. The concept of Spy Mode might look like something “evil” to do – spying on other people’s conversations is an ethical gray area in the real world, but is it online?

The answer to this question depends on how much you know and are aware of privacy online. In theory everything you do online can be (and is) monitored by a number of entities including your ISP (that can read all of your online activity), your operating system and other programs on your machine, a lot of routers on the Internet and at least a few governments. That is all beside the point – I thought about ethics for a second but to be honest I don’t see this as anything but a technological challenge (also, it isn’t illegal per se). My goal wasn’t to spy on people but to hack a bot together and as such I probably only ran the finished script once – to make sure all the bugs were solved. I call it the Hacker’s Mindset :).

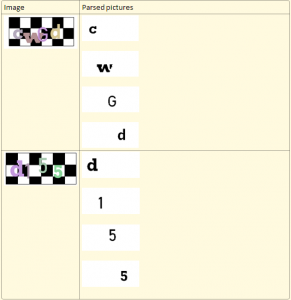

This is how OmegleBot was born. A simple and a very quick and dirty and unrefactored python script. Before that script I didn’t have a lot of knowledge about HTTP, httplib and urllib because I used raw sockets to talk HTTP (poorly) in the past. This was a perfect project to help me understand the python libs relating to HTTP and JSON. The bot opens two simultaneous connections to Omegle and sends them both a simple greeting, “asl?”, which is the way most conversations in chat channels start. It then proceeds to proxy their conversation and also record it into a text file. The most interesting part is the post function. It started as a simple call to connection.request and evolved to include a variety of HTTP headers including a faked user-agent and referer needed to defeat some of Omegle’s “security checks”. Usually services will have more server side security checks (“never trust user input”), but unfortunately Omegle doesn’t have a choice here. Because they are open and allow anonymous chatting it leaves them with only so many ways to ensure I’m a client and I masqueraded as one well. Omegle uses the JSON protocol to pass data about events like whether the other user is typing, the message the user sent and of course when a user disconnects. Reverse engineering it was the hardest part of this project (and it wasn’t all that hard). I think the only challenge I faced was understanding why Omegle blocked the first iterations of the bot and adding various headers until I passed for a client in their book.

I also attached a sample output file with a few conversations. There is nothing interesting there nor did I capture anything interesting. All the conversations are very short which is definitely a symptom of Omegle – long and meaningful conversations are few and far between. I even sent “typing” statuses every few iterations to encourage people to converse and it didn’t help.

What can we learn from this? Masquerading as a browser is easy. Writing bots is easy. As a person on the internet you should take from this that bots are everywhere on the web. You should be aware of that because a lot of spam and fraud is done by bots – you can trivially change this bot to spam

Southpark’s “dey took er jerbs” guy”

(program them, probably)

P.S. Unfortunately the bot stopped working. It can be that Omegle changed the protocol a bit, added some more security or that I have a bug. Feel free to fork it and bring it back to life!